The Argument for Independence

Independence and national identity are emotive issues, but the arguments in favour of a greater level of autonomy for Brittany are very strong and rest upon historical, geographic, cultural, and economic considerations.

Economic Arguments

The myth that has been taught to schoolchildren for the past one hundred years is that Brittany is an intrinsically poor country, hampered by poor soil and bad weather. The real truth, however, is that for most of its history Brittany has been extremely prosperous, and that it only started to go into economic decline once it became united with France.

During the Middle Ages Brittany was one of the wealthiest areas of Europe: the interior was home to a thriving textile industry, and the coastal areas maintained a merchant fleet that was one of the most successful of the age, trading salt, textiles, fish and agricultural products across Northern Europe and down to Spain and Portugal.

The wealth accumulated by these activities attracted the jealousy of neighbouring countries, which is the reason why the King of France forced Anne of Brittany to marry him in 1491, a marriage which eventually led to a union of the two states. Brittany remained semi-autonomous and reasonably prosperous until the Revolution, when it was finally amalgamated into the rest of France. The next hundred years of its history were marked by famines and widespread destitution – giving rise to the short-sighted idea that Brittany has always been impoverished.

Although outwardly prosperous, the modern Breton economy is now dependent on agricultural subsidies and funding from central government – which, in economic terms, is disastrous.

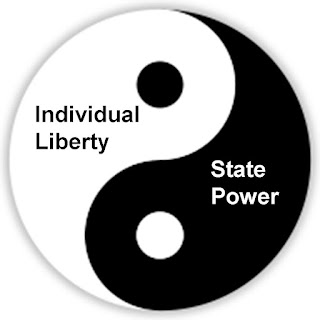

A clear argument can be made that Brittany would be more successful in diversifying its economy and creating wealth, if its people had a greater level of control over their own affairs.

Cultural Arguments

The Breton language has survived to the present time; there is still a tradition of Breton music; and there is a wealth of stories and traditions which are specific to this part of the world. These are the sorts of cultural ingredients which are required to support the sense of identity and common purpose required for a successful unit of government. The idea of an autonomous Brittany makes a lot more sense than many other administrative regions that have been created in Europe and around the world in recent times.

Geographical Arguments

People disagree as to where the eastern border of Brittany ought to lie – for most of the past thousand years Nantes and the ‘Loire Atlantique’ have been part of Brittany – but even a cursory glance of a map of Europe marks the Breton peninsular out as a distinctive geographical area, easily distinguished from the rest of France. Many aspects of life in Brittany are dictated by the weather and the sea, which makes it have more in common with places such as Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall than with mainland Europe.

Historical Arguments

It is, perhaps, history that provides the strongest reasons in favour of a change in the way that Brittany governs itself.

Over the years the people of this region have had many different relationships with the rest of Europe, and there is no reason to suppose that the present arrangement should be regarded as permanent.

In ‘pre-historical’ times, Brittany was inhabited by people about whom we know very little except that they erected the menhirs, dolmens, and covered alleyways that are so common in the Breton countryside. These monuments are quite distinct from remains found in other parts of mainland Europe, but do bear a resemblance to sites in the UK, in India, and in China. This would suggest that, in those days, Brittany was an outward-looking country, more closely allied to countries across the ocean than to its neighbours on the mainland.

Immediately prior to the Roman occupation, Brittany was inhabited by Gallic tribes, each of which was autonomous but loosely linked to other Gallic people by Druids who travelled freely throughout France, Britain, Belgium, Switzerland and northern Italy. The Druids did not constitute a form of government, (or a religion in today’s sense of the word) but do seem to have provided training and spiritual guidance which knitted the Gauls together into a unified nation: it seems unlikely that a tribal chief could have maintained power without the support of the Druids.

Julius Caesar ruthlessly suppressed this civilisation – in modern parlance his ‘campaigns’ would be termed genocide – and Brittany, along with the rest of Gaul, was incorporated into the Roman Empire.

All sense of self-determination was lost over the course of the next four centuries, and, when the Western Empire finally collapsed, the people living in this area had no more idea of how to govern themselves than anyone else in Rome’s former dominions.

But, whereas most of the continent was overrun by tribes from the east (Visigoths, Ostragoths, Huns, Franks, etc.) something unusual happened in Brittany. The Romans had left Britain a few years previously, and it had been settled by people from Saxony: the Saxons. For a time, harmony was established between the native Celts and the newcomers and, consequently, Britain could enjoy a time of peace and prosperity just as chaos was engulfing the rest of Europe. (It is to this period that the legends of King Arthur and Merlin are often dated.)

‘Saints’, or wise men, crossed over from Britain to Brittany and set up sanctuaries in which they taught and helped the local people. The names of some of these men have become legendary and include the ‘Seven Founding Saints’ of Brittany – Malo, Samson, Brieuc, Tugdual, Pol Aurélien, Corentin and Patern.

Towns built up around where they settled (St Brieuc, St Pol de Leon, St Malo, etc.), composed of local people, plus Britons who came to join them. It is only since this time that this region has been known as Brittany and that its people have spoken Breton. It would seem that it is to these founding saints that Brittany owes its traditional love of freedom and independence: Brittany was the only part of modern France which did not fall under the control of Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire, and subsequently Brittany succeeded in resisting a Norman invasion of the type that overwhelmed Britain.

For several centuries Brittany had the status of an independent Duchy, recognised by the Pope in Rome but not allied to any particular kingdom. This independence was lost when Brittany was united with France in 1532. Some modern historians blame this union on the greed of Breton nobles who preferred to accept gifts from the French court than to defending their independence; others have maintained that some form of union was inevitable given the state of European politics at the time. Whatever the case, the young heiress to the Duchy, Anne of Brittany, found herself helpless and besieged by a French army in Rennes and was forced to agree to marry the French king, which signalled the end of Breton independence.

Brittany retained separate institutions (in much the same way as Scotland retained its own legal system after it was united with England), but these were swept away in the French Revolution. Since then Brittany has, administratively, simply been part of France.

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a difficult time for Brittany because the government in Paris had little understanding of the region and no empathy with its history and culture: a legacy with which people are still trying to come to terms today.

The Future

The arguments in favour of Breton devolution are so overwhelming that it is almost inevitable that the region will acquire a greater level of control over it own affairs at some point in the future. The question is when and in what form? Many people are fearful of the phrase ‘Breton independence’ because it conjures up an image of militancy, but, if it is true that Brittany does need a greater degree of autonomy before it can move forward, then it would be those people who defend the status quo that posed the greatest threat to its future.

.jpg)